At last September’s Tomato Fest in Portland, Oregon, tomato enthusiasts gathered to savor the event. Amidst tomato quiche and unique tomato garlands, I headed straight to a yellow booth hosted by Oregon State University. There, agricultural researcher Matt Davis offered samples of experimental tomatoes, each labelled with cryptic codes. I took four small plastic bags, each labelled with a cryptic set of letters and numbers and containing a thick slice of yellow tomato. Scanning a QR code with my phone led me to an online survey with questions about each tomato’s balance of acidity and sweetness, texture, and overall flavor. As I chewed on the slice from the bag marked “d86,” I noted the firm, almost meaty texture. Lacking the wateriness of a typical supermarket tomato, it would hold up beautifully in a salad or on a burger, I thought. And most importantly, it was tasty.

Dry farming, an ancient agricultural practice that does not rely on irrigation, is experiencing a resurgence in the western United States due to increasing water shortages exacerbated by climate change. Although largely abandoned in the 20th century, farmers in the region are now turning to dry farming as a sustainable way to address water scarcity, especially in states like California where agriculture consumes a significant portion of water. While it may not completely solve all agricultural challenges, dry farming offers a promising path forward, particularly for smaller-scale producers, while minimizing the strain on scarce natural resources. Despite some limitations, such as smaller produce and reduced overall harvests, dry farming’s advantages extend beyond water conservation to include longer-lasting and better-tasting produce.

How does dry farming work?

Dry farming is often misunderstood as growing crops without water, but in reality, it involves relying on moisture stored in the ground rather than irrigation. It is feasible in various states across the American West, requiring a wet rainy season to saturate the soil, followed by a dry growing season when plants draw in the stored moisture. Many fruits and vegetables, including tomatoes, potatoes, squash, corn, and even watermelons, can be dry-farmed. Crucial elements for successful dry farming include sufficient annual rainfall (typically over 50 centimeters) and fine-grained soil that retains water effectively.

Farmers use different techniques to ensure crops receive adequate moisture. These include early planting to utilize winter rainwater, wider plant spacing to encourage deeper root growth, and the use of mulch to insulate the soil. Dry farming is a common practice worldwide, from olive groves in the Mediterranean to melon fields in Botswana and vineyards in Chile.

Indigenous peoples have been using dry farming as a traditional method in the American West for thousands of years. For them, dry farming is more than a technique; it is a way of life that embodies their values and spiritual beliefs. The intimate connection with nature that dry farming requires fosters a reciprocal relationship between the cropping system and the farmer. Michael Kotutwa Johnson, a member of the Hopi Tribe, exemplifies this connection as he dry-farms corn, lima beans, and other crops, carrying on the practice taught to him by his grandfather. He emphasizes the beauty and importance of cherishing this ancient farming approach, highlighting the need to respect and learn from the environment that sustains us.

As non-Indigenous settlers arrived in the Western United States, they also adopted dry farming practices. However, with the growth of commercial agriculture in the 20th century, many farmers shifted to irrigation to meet the demands of expanding markets. Irrigation provided better control over the water supply and allowed for increased production and more reliable crop yields.

Nevertheless, the situation has evolved, and today, water scarcity has become a significant challenge for irrigation-based farming in many parts of the West. California’s San Joaquin Valley, the state’s primary agricultural region, faces particular issues with water availability. Water is pumped from deep aquifers and transported through canals and pipelines to irrigate crops. However, during transportation, more than a quarter of the irrigation water can be lost due to evaporation and leaks.

An even more pressing concern is the unsustainable extraction of groundwater. The rate of water withdrawal exceeds the natural replenishment rate, leading to the depletion of aquifers. This results in an insufficient water supply to meet the demands of the extensive farmland in the region. As a result, farmers are now facing water shortages and the need to seek more sustainable alternatives to secure their agricultural activities.

Farmers in California and other western states are facing water shortages, with access to irrigation already restricted, and there have been instances where irrigation has been completely cut off. The situation is not expected to improve in the future, especially with the implementation of California’s Sustainable Groundwater Management Act. The act aims to remove over 200,000 hectares (approximately 10 percent) of irrigated farmland in the San Joaquin Valley by 2040. In response to this challenge, dry farming speciality crops like agave or jujube have been identified as a potentially economically viable alternative for the affected land. A report by the nonprofit Public Policy Institute of California in 2022 highlighted the attractiveness of this option.

In search of water

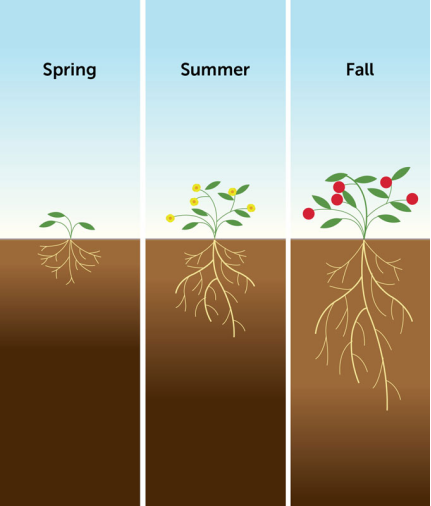

Dry-farmed tomatoes grow longer roots (plant on the left in the photograph) than irrigated tomatoes (plant on the right). Dry-farmed tomatoes are planted early in spring so they can access water in the topsoil (darker brown in the diagram). A lack of irrigation in summer encourages the roots to go searching for water as the soil dries out. By fall, the roots can be more than a meter deep.

Longer-lasting produce is a significant advantage for small-scale fruit and vegetable growers, helping them earn income during slow sales periods like winter. It also reduces food waste, both for farmers and consumers. However, dry farming comes with some drawbacks. It tends to result in smaller fruits and vegetables due to limited irrigation, which may deter some farmers and shoppers who prefer larger produce. Additionally, overall yields are lower as dry-farmed plants produce fewer crops and require more space for their root systems to access water. In comparison to irrigated crops, dry-farmed winter squash, for instance, yielded only 37 to 76 percent as much.

What’s the future of dry farming?

Despite the environmental advantages of dry farming, some farmers remain hesitant to adopt the practice, even for crops with proven success elsewhere. In Oregon, for instance, growers view certain dry-farmed varieties, like Early Girl tomatoes, as elite and expensive due to their smaller size. To assess the economic feasibility of dry farming, researchers are conducting farming trials to identify suitable varieties for commercial production. Focusing on tomatoes, one of the most commonly consumed vegetables in the U.S., they are evaluating factors such as yield, disease susceptibility, and taste to find varieties that flourish without irrigation.

Dry farming is a potential solution for coping with uncertain water resources in the future, but researchers acknowledge that it may not be universally applicable for all crops. As climate change brings hotter and drier summers, some crops may struggle to survive without irrigation, making dry farming riskier in certain regions. Farmers may need to consider switching to crop varieties that are better suited to increasingly arid conditions, favoring species with long, deep roots or those that naturally evolved in arid environments.

Adaptability will be crucial for farmers as they navigate changing climate conditions, allowing nature to guide their choices. Indigenous communities like Johnson’s Hopi Tribe have relied on this approach for thousands of years, raising crops that fit their environment rather than altering the environment to suit the crops. As dry farming becomes more relevant in the face of climate change, embracing traditional and adaptive practices will play a significant role in securing sustainable agriculture in the future.

Citation

J.D. Wetzel. Winter squash: Production and storage of a late witner local food. Graduate thesis at Oregon State University.

[…] Follow our other articles: https://scitechupdate.com/index.php/empowering-agriculture-in-the-western-u-s-through-dry-farming-in… […]

I know this website gives quality dependent posts and additional stuff,

is there any other web site which provides these things in quality?